This page is dedicated in honour of Evander William C Hay

Evander William Cameron Hay

When a crew was formed at an Operational Training Unit the hope would have been that collectively they would be lucky – good at their jobs, an efficient crew, but above all a lucky crew. When Jim Ives’ crew assembled at 30OTU, RAF Hixon two or three of the five were destined to be lucky.

Geoff Yates would complete a full tour of ‘ops’ and when the war ended would be well into his second. Navigator ‘Jock’ Minty was required on the other side of the world to run the family business and left the RAF, w/op Sgt Andrews ‘disappeared’ from the crew and hopefully he too survived the war.

Sadly a/g Stanley Duke succumbed to TB and Ives himself was destined to be killed in action. New navigator James Goodrick and replacement w/op Bill Hay would both prove to be lucky crewmen. Indeed Evander William Cameron Hay would, after a lengthy operational career, be known at his new posting RAF Blackbushe as ‘Lucky’.

Evander Hay was born on 16th December 1922 in Wandsworth, the third child and second son of Catherine Thompson Campbell and George Ross Hay. Evander’s father died on 10th July 1923. George had served his country for seventeen years between 1900 – 1917 in the Argyle and Sutherland Highlanders with periods of service abroad in South Africa, India and then to France in 1914. He was discharged in May 1917 as unfit for further service with a shrapnel wound to his left leg.

1330616 Sgt Evander William C Hay was first mentioned in an Ives log book entry at 1662CU but had probably been with the crew during the early stages of their duty at 27OTU –

Having flown on two completed sorties and two early returns at 625 Squadron with Jimmie Ives Sgt Hay stayed at RAF Kelstern when their crew was split-

Fortuitously Bill Hay was not required for operations on his 21st birthday 16th December 1943. The Ives crew had been split-

Hay resumed operational flying with the crew of P/O Robert Etchells on the raid on Berlin on 1st January 1944. This sortie was abandoned because the ‘port outer exhaust stubs burnt out, starboard outer overheated. Flames leapt over main-

From Alan Croome –

Sgt Hay continued flying with P/O Etchells and over the course of January they completed six more operations –

2nd January –

Etchells and his crew were not on the battle order for operations flown on 20th nor for 21st January – in all likelihood they were enjoying a week’s leave. They were back for the last three operations of the month –

27th January –

For the period following the night of 30th/31st January the moon would be too bright to safely undertake city bombing over Germany. In any event, the weather worsened and no operations would be called until 13th February, which was cancelled.

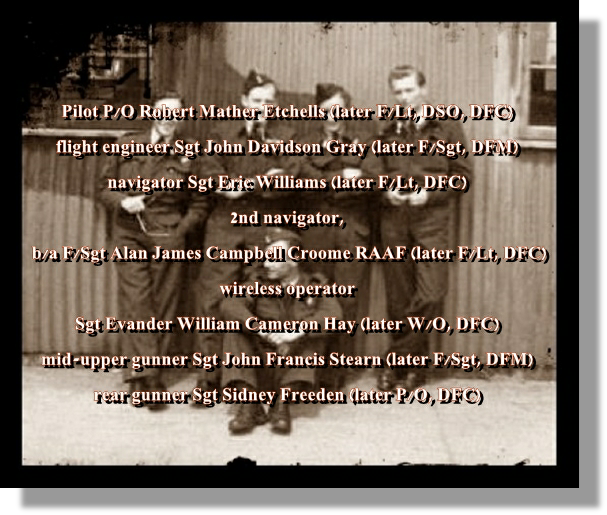

P/O Etchells transferred to the Pathfinders – 156 Squadron w.e.f 9th February 1944 and they flew their first sortie from RAF Upwood (the squadron having moved from RAF Warboys on 5th March) on 15th March (Stuttgart). Between 15th March and 26th August 1944 the Etchells crew operated unchanged on 37 operations.

Between 15th March and 26th August 1944 the Etchells crew operated unchanged on 37 operations.

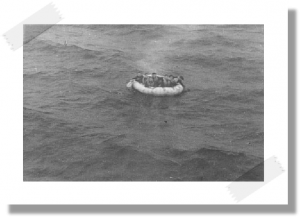

On 26/27th August 1944 Flt Lt R Etchells’s Lancaster was ‘Badly shot about by a Ju88’ over Kiel, ‘but which in turn was last seen going down crippled by the return fire. Soon after the engagement the Lancaster was ditched in the North Sea. There followed an exacting rescue operation involving aircraft, a Danish fishing vessel and an ASR launch before the crew were brought home to Grimsby some five days later.’

The ditching was recounted by Canadian navigator John Goldsmith who had joined the Etchells crew immediately before the operation to take the place of F/Lt Eric Williams their regular navigator who was ill. Goldsmith was on that occasion duty navigator and had had no previous dealings with the crew.

‘It was August 26th 1944. Target was Kiel. Take-

Our own aircraft had been badly damaged. Starboard outer prop shot off. Starboard inner hit and on fire; port tail assembly virtually shot away, a hole 2ft square in the fuselage floor near the rear turret and most of the navigation equipment destroyed. The starboard inner was feathered and the fire put out. Course was now set for North Sea by guesswork. Once over the sea we decided to jettison our marker bombs, then found that the bomb doors would not close. At this stage the port wheel came down and it also could not be retracted. Then the port inner engine caught fire and we began losing height rapidly.

At this stage we knew we would have to ‘ditch’ so crash positions were taken up. I had calculated our position as being some 160 miles from England and 50 miles North of the Friesian Isles which were of course occupied by the Germans. The W/Op tried to send an SOS but the fixed aerial had been shot away and the trailing aerial was earthed against the open bomb doors. So I doubt if any of the crew thought they had long to live. Certainly I know that I didn’t.

Owing to the darkness it was virtually impossible to see the water and we hit it, nose first, with a sudden smash and the aircraft slid along for a short distance on its belly. The noise was terrific and water flew everywhere. We came to a stop with water coming in everywhere. Dinghy drill was carried out very well and we all got out onto the wing OK. The dinghy then put out the sea anchor and decided to wait for daylight before commencing to paddle.

About 02.00 hours we heard an aircraft approaching very low, so we fired off two red flares. The a/c circled us, then dropped a white flare lighting us up, then proceeded on course. This cheered us up no end. Then about 05.00 hours a Lancaster flew low over us and we fired off more red flares. He circled us four times, flashed OK on his downward ident. light and left. By now we were sure we would be picked up soon.

Just a matter of time. We could see the searchlights on the German coasts and had visions of ending up as P.o.Ws. Daylight finally came and we started paddling in the direction of England by means of the small compasses which we all carried. We soon gave this up as we found we were drifting in circles. It was about 11.00 hours when we next heard an aircraft, visibility was poor and we doubted that we could be seen.

After about thirty minutes we saw Air Sea Rescue Hudsons about 5 miles away. We fired off red flares but they seemed not to see these. Then ten minutes later they returned, this time much closer; again we fired off red flares; still without effect. Then the first one turned and, flying very low, came directly towards us; the others followed. They circled and dropped smoke floats to check drift and wind direction preparatory to dropping an airborne lifeboat. Finally one Hudson flew over at about 800 ft and we saw a boat fall out and parachute into the sea.

Unfortunately the mechanism on the boat which was supposed to shoot out a sea anchor failed and in spite of frantic paddling we were unable to reach this. By now our own dinghy had sprung a leak and, with no bellows to top it up, things suddenly took a turn for the worse. Shortly afterwards another of the Hudsons flew over and dropped us a Lindholme Dinghy. This was a dinghy with four containers holding emergency rations, water and flares. This was a good drop and we soon drifted into it.

The R/G jumped into the water to swim towards it but found the seas too cold and we had to retrieve him by the safety rope we had fastened around him. He was practically unconscious when we dragged him aboard. This confirmed our fears that, should we fall out of the dinghy, our chances were very slim. We tied the Lindholme dinghy to our own and with both sea anchors out, three of us transferred to the second dinghy. This made life more comfortable for it had been practically impossible to move with seven of us in one dinghy.

For the rest of the day one of the Hudsons continued to circle us. The weather had by now become overcast and the sea roughened. We were all soaked and miserably cold.

Towards dusk another Hudson approached with an airborne lifeboat which was dropped fairly close to us but it became dark before we could reach this. We stayed awake the whole time because the sea was so rough and we feared we might capsize. Besides which we had to keep baling out the dinghy. Shortly after midnight the moon broke through. It was a beautiful sight and cheered us no end. We soon saw the lifeboat. This time it was fairly close and we managed to reach it after a few hours frantic paddling.

It certainly felt good to climb into it. It was about the size of a large rowboat. It had seven dry, waterproof suits in the lockers which we changed into and threw our own soaked clothing into the sea. There was no room aboard for these. I was elected captain as I had a little knowledge of boats and decided to wait until daylight before setting course as I knew the Hudsons would come out again to us. It was 0.800 hrs when the first one appeared. Later we discovered that a Ju88 had been only one mile from us but flew away on the approach of the Hudsons.

Everything was made shipshape, the two 4h.p engines were started and we set course for England. Within an hour the sea became rough and swamped the engines. They could not be restarted. We could not put up the sail as by now there was a real northerly gale blowing. It is estimated that the wind reached a force of 30-

When the boat had hit the water it had been damaged and under the battering of the heavy seas it began to leak badly and break up. By 14.00 hrs we were almost completely awash. The boat held afloat only by the buoyancy chambers along the deck. Almost everything had been washed overboard and our spirits were at rock bottom. We had given up hope of rescue and most of us were praying hard. We decided that if the boat sank we would tie ourselves together and with our Mae Wests float as long as possible.

Two of the Hudsons were still circling us but their efforts seemed futile. It was about 16.00hrs when Bob, the pilot, yelled “A ship!” I didn’t believe it at first, but sure enough it was a sailing boat being guided to us by the aircraft. When it got closer we saw it was a Danish fishing boat and I would say that it was the most beautiful sight I had ever, or will ever, see.

It was quite an effort getting aboard owing to the rough seas, but we finally made it. We were so relieved we just lay on the deck trying to realise how lucky we were. There were four men on board, one had fished out of Grimsby before the war and could speak a little English. We asked where he was heading and he said he had finished fishing and was headed home.

We suggested him taking us to Sweden where we hoped for better treatment than from the Germans who would capture us on our landing in Denmark. He said that it was impossible. When we said “England” he merely smiled. One of the Hudsons then flew low and dropped a container with the message “Steer course of 250 degrees for England”. This worried the Danes and they argued among themselves for about five minutes then started turning around.

One of us saw the compass and we were on a course of 250 so all looked well. The Danes had apparently accepted the situation. They took us down to the cabin and lighted the stove, we dried ourselves and donned the dry clothes they provided us with. We were told to use their bunks and we soon were fast asleep.

In the morning although I felt better I found I was almost too weak to stand. It had been a foul night which had forced the boat to heave to until daylight. One of the Danes brought us some food. Canned meat and fish, German bread, which tasted of sawdust, and ersatz tea, this tasted great to us being the first hot drink for over two days. I doubt we could drink it now as it had no resemblance to tea.

During the day we tried to teach the Danes a little English and vice versa. The one who could speak English told us much about Denmark and the Germans. They had an excellent wireless receiver on board and we listened to everything from German propaganda to Bing Crosby. We found it very amusing when the Danes started shaving two weeks growth of beard preparatory to arriving in England.

It was 17.00 hrs when we were met by the Air Sea Rescue Launch. They told us they had been very close to us the day after we ditched but had lost contact with the aircraft and mechanical breakdown had forced

Etchells crew in their dinghy, photographed by ASR Boston Crew.

Alan Croome :-

Several photographs of the ditched crew were taken by Air Sea Rescue aircraft and are held by the Imperial War Museum. The Kiel sortie marked the end of operational tours for the Etchells crew and John Goldsmith too, a finale which had surely been an incredibly harrowing experience for all concerned.

When the crew was disbanded each received decorations for their devotion to duty at 156 Squadron and in recognition of their escape from the North Sea ditching. The crew involved in the North Sea rescue also became members of the ‘Goldfish Club’.

W/O Bill Hay was awarded the DFC on 31/12/1944 and following a spell of survivor’s leave was posted to RAF Blackbushe for a deserved rest. By the end of 1944, 167 Squadron of RAF Transport Command was stationed at Blackbushe together with units operating De Havilland Mosquitoes. 167 Squadron flew Vickers Warwicks from November 1944 on regular services to and from various bases in Europe and North Africa. Warwick Mk IIIs could carry 24 troops or 8-

It is not possible to confirm how much flying W/O E W Hay DFC did while at RAF Blackbushe as Bill lost his flying log-

Despite this minor mishap Bill became known by his colleagues at Blackbushe as ‘Lucky’-

Bill Hay and Jessie Knott met at a pub near Blackbushe airfield, Bill being with a group of his friends, Jessie with some WAAF pals. Jessie, or Cissie as she is known in the family, had joined the WAAF having used her elder sister Gwen’s papers and had completed her training in Scotland before her mother managed to find out how to challenge her daughter’s enlistment, by which time she was not long from being of age. Her mother’s appeal was unsuccessful and Cissie continued her service. When they met Bill asked Ciss if he could walk her back to her lodgings, seeing that everyone else had paired off –

After the war Bill Hay continued to use his skills in civil aviation, at Hounslow / Heathrow and then in the South West of England.

Evander William Cameron Hay died in February 2002 aged 79, Weston, North Somerset.

In 2012 a copy of Bill’s photo was sent to Geoff Yates who confirmed that, yes –

‘by his smile.’